JABSOM Convocation 2024

In middle school, I asked for a neuroscience textbook for Christmas. I understood maybe a few pages, but I loved the pictures. In high school, I asked for a neuroanatomy atlas. I can still hear my mother going “Mhmmmm” when I’d tell her the brain area she used if she so much as moved her pinky. In college, I planned to transform this fascination into a career committed to the betterment of others. And so, I came to Stanford Medicine thinking I’d be a surgeon, bringing to life my neuroscience flashcards in the operating room.

Having now completed my surgery clerkship, that is unlikely.

As it turns out, donning scrubs, gloves and a mask to watch a surgeon is not the same as actively living the life of one. Coming in to observe the highs of a surgical case is not the same as scrambling to respond to an unexpected complication.

It’s not the same as the hours of training required, or the type of mental fortitude needed to work case after case. It’s not the same as spending so much time on your feet that they go numb. Years as a fascinated bystander failed to prepare me for the unique culture and mindset of the surgical world. While some of my classmates relished it, I was lost. Queue panic calls to friends and family who assured me everything happens for a reason. But, after every conversation I was left with a bitter taste — why couldn’t I let go?

I’ve realized my unrest was largely because my self-worth was linked too closely to the notion of prestige and the self-pride I’d derived by identifying as a future surgeon. I certainly garner personal fulfillment through other sources, but to deny the contribution of prestige is to deny my current reality.

Oddly enough, it’s in living the life of a surgeon that I’ve learned prestige feels good at the dinner table but falls short to sustain and cultivate my daily emotional and physical needs. It’s loud and proud when discussing job prospects with family and friends, yet silent when I’m so exhausted even blinking is hard.

And so, the last six months were spent reconnecting with the reasons I came to Stanford. I challenged myself to re-answer why I entered medicine and to do so, I was forced to reexamine where I’ve come from, who I am, and where I want to go. This complemented efforts to restructure my goals around these reestablished values and life objectives. The process was unnerving but resulted in a clarity I hope to bring to all my work moving forward — I now understand that personal fulfillment is better derived internally than externally. When we are internally fulfilled, when we provide to the world, we draw energy from who we are rather than what we wish we were.

It is with this understanding that I leave surgery behind and hope to enter psychiatry as a career. This is not to say anything about psychiatry or surgery as careers and is to say something about psychiatry and surgery as careers for me, taking fully into consideration the context of who I am, where I’m going and why I’ve entered medicine.

In living the life of a psychiatrist, I’ve learned it’s a field where the culture, mindset, and focus more suit what nurtures my own sense of fulfillment. It’s where I can bring to life my picture books and flashcards in the stories and lives of my patients. It’s where the patients may feel our efforts validate their lived experience, but it’s really they who validate ours. I see now that in living the life of a psychiatrist, the prestige isn’t gone, it’s just found a home in my heart rather than as a topic at the dinner table.

Jon Sole is a fourth-year medical student at Stanford. He loves neuroscience, quality improvement, technology, and anything remotely related to their intersect.

22-year-old man presented with 10 years of retrosternal burning and suspected gastroesophageal reflux. Despite taking omeprazole (20 mg once daily) 30 minutes before breakfast, avoiding foods that precipitated symptoms, and sleeping with his head elevated, heartburn and regurgitation while supine continued. He reported intermittent solid-food dysphagia for 2 years but no weight loss (254-lb [115 kg] body weight); physical examination results were unremarkable.

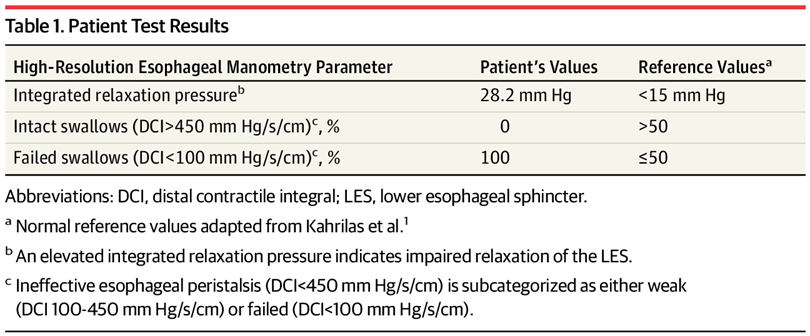

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed normal esophageal mucosa and normal biopsies. Given his persisting symptoms, an esophageal high-resolution manometry (HRM) study was performed (Table 1; eFigure in the Supplement).

Patient Test Results

DiscussionAnswer

B. Perform esophageal (Heller) myotomy and partial fundoplication.Test Characteristics

GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease) can present at any age. HRM is not necessary for most patients with GERD, but it is indicated for evaluating esophageal motor function in patients with persistent esophageal symptoms (dysphagia, heartburn, regurgitation) that are unresponsive to antireflux medication and are not explained by diagnostic testing with endoscopy or contrast radiography. HRM is also used to identify the location of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) for positioning of ambulatory reflux monitoring catheters and for assessing esophageal peristalsis prior to fundoplication. In contrast to the 5 to 8 recording sites with conventional esophageal manometry, HRM uses a catheter embedded with 20 to 36 closely spaced circumferential pressure sensors inserted transnasally into the stomach, spanning the entire esophagus. Medications that can affect esophageal smooth muscle function (ie, calcium channel blockers, nitrates, metoclopramide, opioids) are stopped whenever possible. A standard HRM protocol typically involves 10 wet swallows (in which 5 mL of ambient temperature water is swallowed on cue).

Raw pressure data from each swallow are transformed by HRM software into topographic color-coded pressure contour plots (Clouse plots). Chicago Classification (version 3) describes esophageal motor function using 3 software metrics: integrated relaxation pressure (IRP; measures adequacy of LES relaxation for swallowed content to pass through), distal contractile integral (DCI; quantifies vigor of smooth muscle peristalsis), and distal latency (DL; identifies appropriate sequencing of peristalsis). An IRP of greater than 15 mm Hg has a sensitivity of 93% to 98% and a specificity of 96% to 98% for a diagnosis of achalasia (defined as lack of LES relaxation with absent or abnormal esophageal body peristalsis).

In 2018, Medicare paid $144.86 for HRM studies.Application of Test Results to This Patient

In this patient, HRM revealed absent esophageal peristalsis and median IRP of greater than 15 mm Hg (Table 1; eFigure in the Supplement), which indicated no LES relaxation with swallows, and a diagnosis of achalasia. Achalasia type II consists of failed LES relaxation resulting in obstruction at the esophagogastric junction and increased intraluminal pressure throughout the esophagus with swallows.

This patient with achalasia presented with symptoms similar to GERD. EGD was normal, and esophageal symptoms persisted despite acid suppressive therapy. In this setting, at least 30% of patients have alternate diagnoses, such as functional heartburn (heartburn without objective evidence of GERD, eosinophilic esophagitis, or major motor disorders), achalasia, or rumination syndrome (effortless, volitional postprandial regurgitation of undigested food from the stomach). As many as 2% to 3% of patients undergoing HRM prior to antireflux surgery have evidence of achalasia, when fundoplication without LES disruption will exacerbate obstruction from the incompletely relaxing LES.7 Therefore, HRM is important in the evaluation of persistent esophageal symptoms not responding to standard GERD therapy.

Although achalasia and GERD can present with similar retrosternal burning and/or regurgitation, management is different. Disruption of the LES (using graded pneumatic dilation, surgical myotomy, or per-oral endoscopic myotomy) effectively treats achalasia symptoms. In contrast, augmentation of the LES with fundoplication is useful when documented GERD persists, despite medical management. Establishing this distinction between achalasia and GERD is important prior to surgical intervention, and HRM establishes this distinction.Alternative Diagnostic Testing Approaches

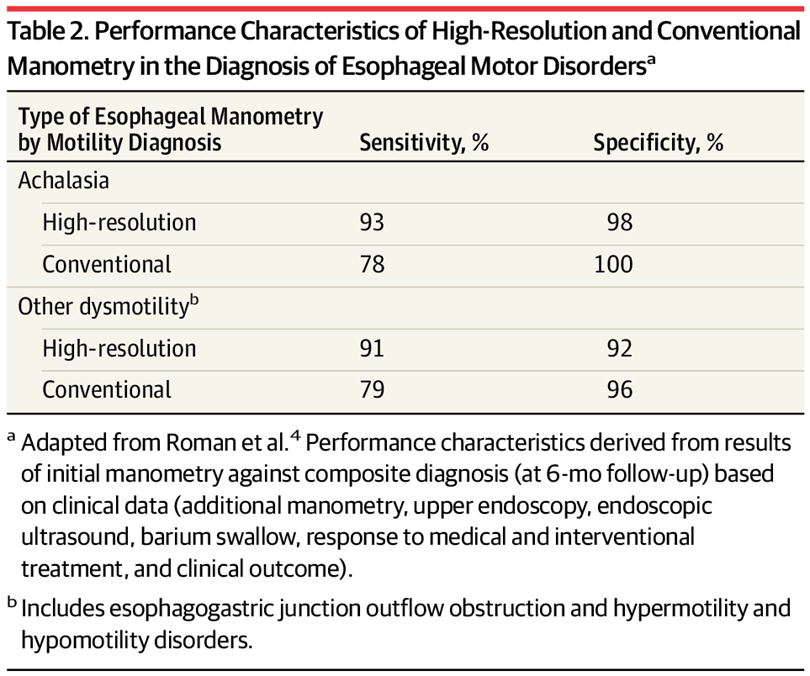

When evaluating esophageal motor function, HRM is more accurate than conventional manometry in diagnosing achalasia. Conventional manometry may not identify abnormal LES relaxation if the recording sensors are not precisely positioned, potentially increasing cost from missed achalasia diagnoses. Esophageal HRM has largely replaced conventional manometry due to increased diagnostic accuracy, better reproducibility, and ease of interpretation.Table 2.

Performance Characteristics of High-Resolution and Conventional Manometry in the Diagnosis of Esophageal Motor Disordersa

EGD is integral to the evaluation of dysphagia and persistent heartburn to rule out mechanical obstruction (such as eosinophilic esophagitis, stricture, or malignancy), but EGD does not reliably assess esophageal motor function and only identifies achalasia in one-third of patients with the diagnosis. A timed barium swallow with barium column height of 5 cm at 1 minute has a sensitivity of 94% but a specificity of only 76% in diagnosing achalasia.Patient Outcome

This patient underwent an uncomplicated laparoscopic Heller myotomy with partial fundoplication. Eight years later, his heartburn, regurgitation, and dysphagia symptoms had resolved.

Source: AMA Wire

Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation scientists have pinpointed a cell that begins the process of scarring in fatty tissue. The findings cast new light on a biological process that occurs with obesity and can lead to diabetes.

carring can be an important part of the healing process when a person suffers an injury,” said OMRF’s Lorin Olson, Ph.D., who led the research. “But excessive scarring, or fibrosis, can contribute to many dangerous health conditions.”

The new research appears in the June 1 issue of the journal Genes & Development.

Using experimental models, Olson and his team found that by stimulating a particular growth factor (known as platelet-derived growth factor, or PDGF) that occurs naturally in the body, they could cause certain undifferentiated cells to develop into scar tissue. But when the researchers didn’t activate the growth factor, those cells continued on their normal fate and became fat cells.

Injured or stressed tissues produce PDGF, which stimulates wound repair. However, too much of the growth factor leads to scar tissue, so the body needs a balance of PDGF activity for proper tissue repair.

Fibrosis can also be an early event in the disease process leading to diabetes, which, according to the American Diabetes Association, affects nearly 30 million Americans.

“When fat cells are surrounded by scar tissue, it inhibits their ability to store lipids,” said Olson. “When that happens, the lipids are stored in places like the liver or muscle. That can cause insulin resistance, which can lead to diabetes.”

In future studies, Olson will examine the PDGF pathway and how it disrupts the fate of the fat cells. “By studying the molecular mechanisms involved in the process, we’ll try to understand the role it may play in heart disease, diabetes and other metabolic disorders.”

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation. Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.